Adults

Let’s take a look back over the years at some of the hardware and software I worked with at Mid-Manhattan Library.

Middle to late 1980s

IBM PC, XT and AT models with 128 -256 KB memory; 1 or 2 floppy 360K disk drives;

12″ monochrome green monitor; keyboard; 10-20 MB hard drive (optional);

DOS 3.0-4.0; $2,500 or more.

Today is the ingenious Dr. Franklin’s birthday, and in his honor I’d like to suggest that you come to the Library and browse our digital collection of his works. At any branch or research library in the NYPL system, you can browse the Early American Imprints (Series I) database for works written or printed by Franklin. And this database allows you to read, print, and save for yourself the full text images of any books, pamphlets, broadsides and periodicals that strike your fancy.

Another option for Franklinophiles out there is a visit the Grolier Club, which currently has on offer an exhibition called Benjamin Franklin, Writer and Printer. The curators, James N. Green and Peter Stallybrass, are scheduled to give a lecture on their exhibition at 2:00pm on January 23rd. And NYPL holds a copy of the curators’ accompanying book, so you can come long after the lecture and exhibition have passed and still take it all in. There’s plenty of Franklin to go around, as you’ll see, and I’m willing to share. Happy Birthday!

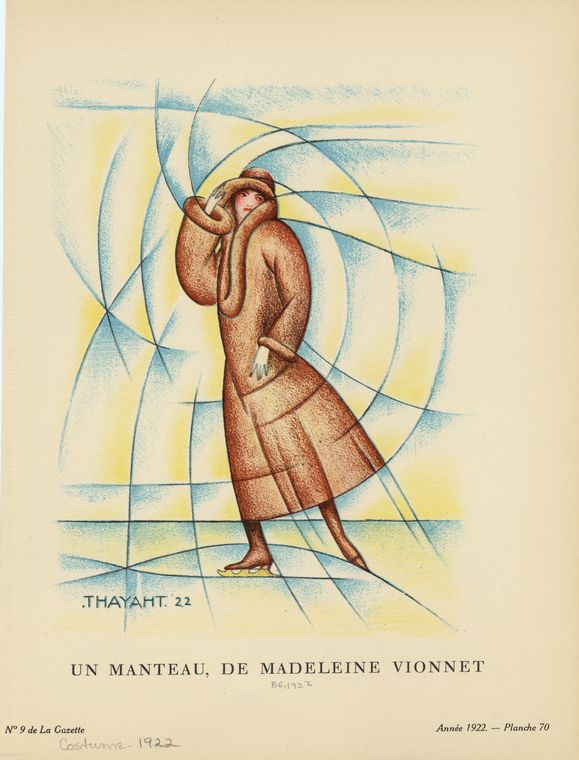

Part of the visual appeal of Art Deco design at this time is in the use of pochoir, or color stencil printing. Have a look in the Library's Digital Gallery at the illustrations of Jean Saude, done for his book, Traite d'enluminure d'art au pochoir. Women were entering a period when their gender could reap the benefits of modernity. Consider the fact that two of the most fascinating women of 1920s pop culture were Josephine Baker and Clara Bow!

“No place affords a more striking conviction of the vanity of human hopes than a public library; for who can see the wall crowded on every side by mighty volumes, the works of laborious meditations and accurate inquiry, now scarcely known but by the catalogue…”— Samuel Johnson Rambler #106 (March 23, 1751)

[img_assist|nid=54759|title=New Grub Street|desc=|link=url|url=https://catalog.nypl.org/search/v1398822|align=right|width=224|height=350]I’m a little less than halfway through George Gissing’s New Grub Street (1891), a delightfully gloomy late Victorian novel about (among other things) the writer’s life and the uneasy relationship between art and commerce. It’s a remarkably well written, insightful and contemporary-feeling book, one that came highly recommended from friend of a friend. Interestingly enough, this book has been the subject of an issue of Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor [”Grubstreet U.S.A.” American Splendor No. 11, see also]

I haven’t gotten to the end of it yet, so I can’t talk about the book with any real authority (not that I’ll be able to do so after reading it either). Nonetheless, I’d like to share with everyone a passage that I came across (in chapter VIII) that has to do with the main reading room of the British Museum. It provides a nice description of what I’ve oftened imagined to be the inner life of some of the people here at Mid-Manhattan (the ones with their heads down on the tables), and also offers a wonderfully inventive and funny riff on the maddening, almost mechanical way that the books here in The Library beget other books, which beget other books, which …

I didn’t expect to find in books of this era a passage so light and grim at the same time - it’s sort of like the Sorcerer’s Appretice segment in Disney’s Fantasia, meets Thomas Malthus, meets Rube Goldberg, meets the Espresso Book Machine, meets …

You get the point. Here’s the passage:

“… The days darkened. Through November rains and fogs Marian [Yule, the daughter of (and researcher for) a bitter and somewhat unsuccessful writer/editor] went her usual way to the Museum, and toiled there among the other toilers. Perhaps once a week she allowed herself to stray about the alleys of the Reading-room, scanning furtively those who sat at the desks [for the young, up-and-coming writer Jasper Milvain], but the face she might perchance have discovered was not there.

One day at the end of the month she sat with books open before her, but by no effort could fix her attention upon them. It was gloomy, and one could scarcely see to read; a taste of fog grew perceptible in the warm, headachy air. Such profound discouragement possessed her that she could not even maintain the pretence of study; heedless whether anyone observed her, she let her hands fall and her head droop. She kept asking herself what was the use and purpose of such a life as she was condemned to lead. When already there was more good literature in the world than any mortal could cope with in his lifetime, here was she exhausting herself in the manufacture of printed stuff which no one even pretended to be more than a commodity for the day’s market. What unspeakable folly! To write — was not that the joy and the privilege of one who had an urgent message for the world?Her father, she knew well, had no such message; he had abandoned all thought of original production, and only wrote about writing.

She herself would throw away her pen with joy but for the need of earning money. And all these people about her, what aim had they save to make new books out of those already existing, that yet newer books might in turn be made out of theirs? This huge library, growing into unwieldiness, threatening to become a trackless desert of print — how intolerably it weighed upon the spirit!

Oh, to go forth and labour with one’s hands, to do any poorest, commonest work of which the world had truly need! It was ignoble to sit here and support the paltry pretence of intellectual dignity. A few days ago her startled eye had caught an advertisement in the newspaper, headed ‘Literary Machine’; had it then been invented at last, some automaton to supply the place of such poor creatures as herself to turn out books and articles? Alas! the machine was only one for holding volumes conveniently, that the work of literary manufacture might be physically lightened. But surely before long some Edison would make the true automaton; the problem must be comparatively such a simple one. Only to throw in a given number of old books, and have them reduced, blended, modernised into a single one for to-day’s consumption. …”

Using images from the Library's collections, I'll start tracking some of the ideas and inspirations for fashion change that happened in those fast-moving decades. I think it will be eye-opening for many... The design by Madeleine Vionnet above is typical. She was one of Art Deco's first patrons, along with other haute couture designers.

Speaking of eye-opening, I was searching AOL this weekend and discovered another piece of evidence that everything old is new again. If you look for the term Padded Butt Boxer Brief online, available also on eBAY, you'll find a male enhancement corsetry item that was originally used back in the 18th and 19th century by men who wanted to fill their skintight breeches better.

It’s always exciting to see citations to the holdings of the Music Division of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts in newly published books and articles. But it’s even more exciting when a newly-published score is based on one of our manuscripts.

The latest volume of the new Works of Gioachino Rossini edition (entitled “Chamber Music Without Piano”) contains several works, among them the Serenata. Composed in 1823 “for his friend Vincenzo Bianchi” (and first published in 1828) there are only two manuscript sources for this work, neither in the hand of the composer. The earlier (and primary source) is located in the Biblioteca del Conservatorio “G. Verdi” in Milan. The editors of the Works of Gioachino Rossini edition describe our copy as being a copy of the earlier manuscript. In fact, the two manuscripts are “linked” in that markings in the Milan manuscript correspond to page turns in our manuscript.

Our manuscript probably stems from the latter half of the 19th century (based on the highly acidic paper on which it is written). The property stamp of Sam Franko (of the family that began the Goldman Band, still active today in New York City) indicates that it was probably picked up by him on one of his sojourns in Europe. As stated in the critical notes, he never appears to have played it for his concerts, and donated the manuscript to The New York Public Library’s Music Division in 1919, where it was first cataloged the following year.

Even in my brief time as curator, quite a number of people have expressed interest in this work. So the Works of Gioachino Rossini edition have satisfied a great need by publishing it in an excellent new edition.

![[Men In Suits And Woman Wearing Jacket, United States, 1920s.], Digital ID 817187, New York Public Library [Men In Suits And Woman Wearing Jacket, United States, 1920s.], Digital ID 817187, New York Public Library](https://images.nypl.org/?id=817187&t=w)

In the months ahead, I'll be looking at key aspects of decorative style versus personal style, and how they parallel fashions in design. I'll also be investigating a theory that is bubbling away inside me - that much of what we define as modern fashions are truly rooted in the exciting and turbulent decades of the 1920s and 1930s.

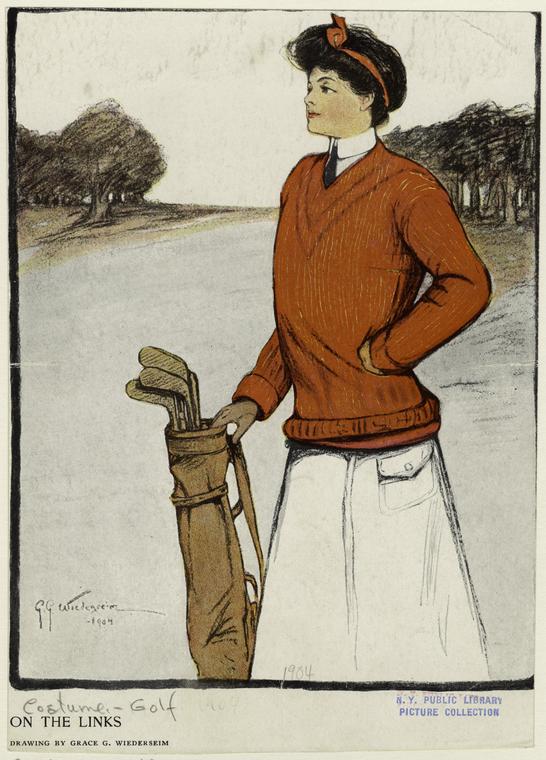

Leave to it P. G. Wodehouse, comic genius and creator of The Inimitable Jeeves and Wooster, to bring levity to my growing obsession with wartime knitters. Lately I have been reading The Clicking of Cuthbert, a collection of Wodehouse’s golf tales. And let me add here: even if you, like me, know nothing of golf, you can still embrace these comedies set among the niblicks and mashies. Included in this volume is a cautionary tale about two rival golfing men, one stout and one lean, who attempt to guess which of them is favored by a certain young lady by studying the size of the item she is knitting. The assumption that they make is that she’s knitting for one of them. Of course, since this tale is by Wodehouse nothing turns out as these golfing gallants might expect. And Wodehouse includes the following warning, concerning the risks of amateur knitting:

“With amateur knitters there must always be allowed a margin for involuntary error. There were many cases during the war where our girls sent sweaters to their sweethearts which would have induced strangulation in their young brothers.”

If Wodehouse’s humor is your style, then check out NYPL's holdings for this prolific writer, musician, and essayist. A quick author search for him (Wodehouse, P. G. (Pelham Grenville), 1881-1975.) will point the way. On that note, toodle pip!

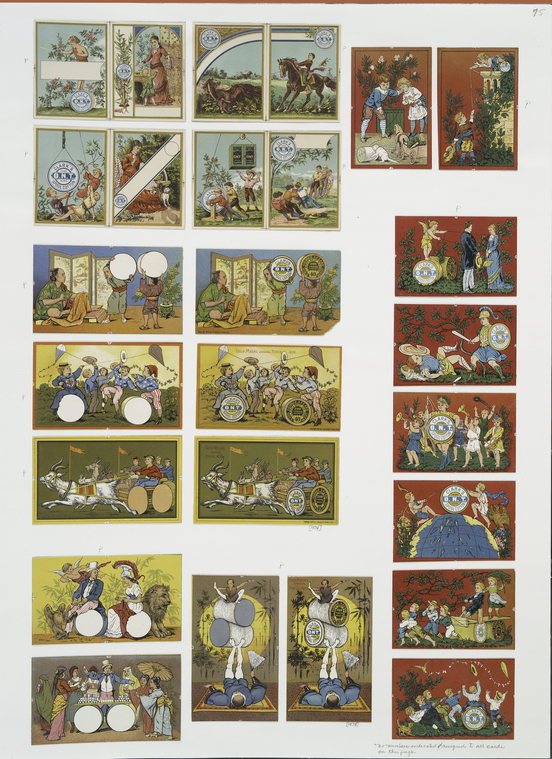

Chances are, if you own some spools of thread or hanks of embroidery floss, then you own some products created by the Coats & Clark Company. Their thread—for sewing, quilting, embroidering, and more—is sold everywhere. After picking up a fresh supply of Coats & Clark Dual Duty thread a few weeks ago for a dress, my curiosity was piqued. Who are these Coats and these Clarks?

As I learned, Coats & Clark started out in the nineteenth century as two independent companies, and the two did not merge until 1952. Coats had mills in Paisley, Scotland, and in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, while Clark was based in Newark, New Jersey. And it was George Clark who revolutionized home sewing with the invention of the first thread that would work reliably in sewing machines. Clark marketed this new thread as “Our New Thread,” a tagline that would be shortened over the years to become “O.N.T.”

The Library holds several small pattern books published by Clark between 1916 and 1919, and each includes O.N.T. in its title. For instance, there’s Clark’s O.N.T. “Woolsaver” Knitting and Crochet Book” (1918), in which I learned that Woolsaver Cotton, available in military hues of “olive drab, navy blue, and grey,” was made to be used along with wool “to strengthen and prolong the life of knitted articles” while there remains an “urgent need to conserve the wool supply for Our Boys at the front.” You can find the other Clark’s O.N.T. books by searching in Catnyp for “Clark’s O.N.T.” as a title.

And if you are curious, you can learn a bit more company history at the Coats & Clark website. The site offers free patterns as well.