|

Charles Dickens: The Life of the Author

The Great Magician VanishesDickens, who had long maintained that if at all possible he must "die in the harness," was happiest when pushing himself to the absolute extremes of his physical and mental endurance. And so, with his health failing steadily, and feeling he could no longer endure the rigors of touring (the horrors of rail travel!), he decided to present a final, but still very ambitious series of "Farewell Readings," which commenced on the evening of October 6, 1868, at London's St. James's Hall, with a program devoted to Doctor Marigold (from the Christmas story) and The Trial from Pickwick. He had settled with Chappell & Co., the tour managers, on 100 readings for the princely sum of eight thousand pounds; printed programs and Chappell's advertisements included the following statement:

Evening performances generally began at 8 p.m. and lasted about two hours; programs nearly always consisted of a long and richly dramatic piece, such as the reading from A Christmas Carol, followed by a shorter and more broadly comic "scene" like The Trial from Pickwick or Mrs. Gamp. The cost of seats had remained fairly constant over the years. For the programs at St. James's Hall, the stalls were priced at five shillings, balcony seats at three, and general admission at one shilling. A new amenity, sofa stalls ("of which there will be a limited number only"), went for seven shillings. Prices could be higher at certain venues. At Brighton, for example, "a few Fauteuils reserved at One Guinea each" were made available in "compliance with the suggestion of some ... patrons." Two Macbeths!  of Dickens's letter to his Swiss friend Monsieur De Cerjat, which was written on January 4, 1869, on the eve of the public premiere of Sikes and Nancy (the envelope is shown here). Of seeing Lausanne again, Dickens is doubtful: "I don't seem in the way of it at present; for the older I get, the more I do, and the harder I work." NYPL, Berg Collection After attending a later performance of Sikes and Nancy, the great Macready told Dickens (who was thrilled by the comparison): "it comes to this--er--TWO MACBETHS!" Dickens savored every moment, every horror-stricken face in the house, pouring into his performance the nervous excitement and energy that he should have been husbanding. "It is quite a new sensation," he said, "to be execrated with that unanimity, and I hope it will remain so!" He enacted Sikes and Nancy with such ferocity that after some performances he was unable to move. His advisers deplored the exhausting effects of the reading, some fearing that it would lead Dickens to an early grave. On January 4, 1869, on the eve of the first public performance of Sikes and Nancy, Dickens wrote to his old Swiss friend William F. De Cerjat: I will answer your question first. Have I done with my Farewell Readings? Lord bless you, No; and I shall think myself well out of it, if I get done by the end of May. I have undertaken 103, and have as yet vanquished only 28. Tomorrow night, I read in London, for the first time, the Murder from Oliver Twist which I have re-arranged for the purpose. Next day I start for Dublin and Belfast; I am just back from Scotland for a few Christmas holidays; I go back there next month; and in the meantime and afterwards go everywhere else. Then follow some comments on a number of subjects, including: the Church of Rome and its "aspirations and encroachments;" the question of Ireland and the "powerful Irish-American body;" various family matters, such as the health of his son-in-law Charles Collins (who eats well, but "that is about the only sign of a natural or healthy condition that can be detected in him"); the new Thames embankment; and, finally, the state of his own health, Dickens disingenuously informing M. De. Cerjat merely that he has had "a few occasional reminders of his 'true American Catarrh.'" He then closes the letter proper with some final thoughts, and with perhaps a passing grumble about his demanding schedule, which of course he has imposed upon himself: I like to read your Patriarchal account of yourself among your Swiss vines and figtrees. You wouldn't recognize Gads Hill now; I have so changed it, and bought land about it. And yet I often think that if Mary were to marry (which she won't), I should sell it, and go genteelly vagabonding over the face of the Earth. Then indeed I might see Lausanne again.--But I don't seem in the way of it at present; for the older I get, the more I do, and the harder I work.

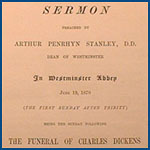

Farewell to the garish lights The arrangements were first announced to the public in the pages of All the Year Round, on July 31, 1869: "Mr. Charles Dickens, having some time since become perfectly restored in health, will resume and conclude his interrupted series of FAREWELL READINGS ..." The advertisement would then run every Saturday in the journal until the conclusion of the series.  in evening dress and with the inevitable red carnation in his buttonhole, at the last of his " Farewell Readings," at St. James's Hall in London on March 15, 1870, from the March 19 issue of the Illustrated London News. NYPL, Print Collection On March 19, the Illustrated London News reviewed Dickens's "ever-memorable farewell reading" with the greatest respect and affection, observing that those "who have been accustomed to attend his readings will regret their termination." Featuring an illustration of Dickens at his reading desk on that unforgettable evening, the article also reproduced the brief and gracious curtain speech with which he brought the reading--and indeed a theatrical era--to an end: It would be worse than idle, for it would be hypocritical and unfeeling, if I were to disguise that I close this episode of my life with feelings of very considerable pain. For some fifteen years, in this hall and in many kindred places, I have had the honour of presenting my own cherished ideas before you for your recognition, and, in closely observing your reception of them, have enjoyed an amount of artistic delight and instruction which perhaps it is given to few men to know ... Nevertheless, I have thought it well at the full floodtide of your favour to retire upon those older associations between us which date from much further back than these, and henceforth to devote myself exclusively to the art that first brought us together. Ladies and Gentlemen, in but two short weeks from this time I hope that you may enter, in your own homes, on a new series of readings at which my assistance will be indispensable; but from these garish lights I vanish now for evermore, with one heartfelt, grateful, respectful, and affectionate farewell. Thus, with his customary panache, Dickens bade farewell to the public that adored him, while simultaneously directing its attention to the forthcoming appearance of his latest novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood--that "new series of readings," as he playfully put it, "at which my assistance will be indispensable." The American magazine Every Saturday published the first installment of The Mystery of Edwin Drood in its issue of April 9, 1870. Accompanying that number was a special double-page engraving by Sol Eytinge, Jr., titled "Mr. Pickwick's Reception," in which the artist ingeniously placed a procession of Dickens's chief characters, "that vast and variously gifted family," before Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller, who are given the place of honor in the cartoon "on account of their priority." The editors of Every Saturday assured their readers that no key was required "to the perfect elucidation of the picture," and that: ... one may pass half an hour very agreeably in naming to one's self the originals of the various portraits in this compact Dickens Gallery. They are all old, and many of them very dear, acquaintances,--excepting, to be sure, the unknown energetic gentleman in the background, who appears on horseback, with the trumpet in one hand, and in the other a banner with a strange device. He seems to be ushering to the scene a troop of shadowy figures,--vague, indefinite sort of people as yet, but people to whom we are predisposed to give a warm welcome, feeling convinced that we shall take some of them to our hearts and homes long before we have solved "The Mystery of Edwin Drood." Famously, of course, Edwin Drood remains a mystery that will never be solved.  completed by Dickens of The Mystery of Edwin Drood, published by Chapman and Hall in September 1870. The illustrated wrapper was designed by Dickens's son-in-law Charles Collins, who was to have done the plates as well (when his health gave out, he was replaced by the young Luke Fildes). NYPL, Berg Collection Less than three months after the final reading at St. James's Hall, Dickens suffered a massive stroke at Gad's Hill Place, the beautiful home he had dreamt of owning as a boy. He died the following day, on June 9, 1870, never having regained consciousness. Only six of the twelve projected numbers of Edwin Drood had been completed. "I never knew an author's death," Longfellow wrote to Forster from America, "to cause such general mourning. It is no exaggeration to say that this whole country is stricken with grief." He was buried in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey, an artist of supreme poetic power who had captured the hearts and imaginations of the world as few writers had ever done. There is in truth something overwhelming about Dickens. It is as if he rises above the dictates of art. "Something larger seems involved," said Chesterton, "which is not literature, but life." After dispensing with his various properties, monies and possessions (including his copyrights), as well as with the manner of his burial ("inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private"), Dickens's will closed: "I rest my claims to the remembrance of my country upon my published works, and to the remembrance of my friends upon their experience of me in addition thereto. I commit my soul to the mercy of God through our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and I exhort my dear children humbly to try to guide themselves by the teaching of the New Testament in its broad spirit, and to put no faith in any man's narrow construction of its letter here or there." Just a few weeks before his final collapse, Dickens was walking with a dear friend, when he suddenly asked his companion to guess what had long been one of his own most cherished daydreams. Without waiting for a reply, Dickens said: "To settle down now for the remainder of my life within easy distance of a great theatre, in the direction of which I should hold supreme authority. It should be a house, of course, having a skilled and noble company, and one in every way magnificently appointed. The pieces acted should be dealt with according to my pleasure, and touched up here and there in obedience to my own judgment; the players as well as the plays being absolutely under my command." And then he laughed: "There, that's my daydream!"

|

||||||||||||||