About the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building is part of The New York Public Library, which consists of 92 locations across the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island.

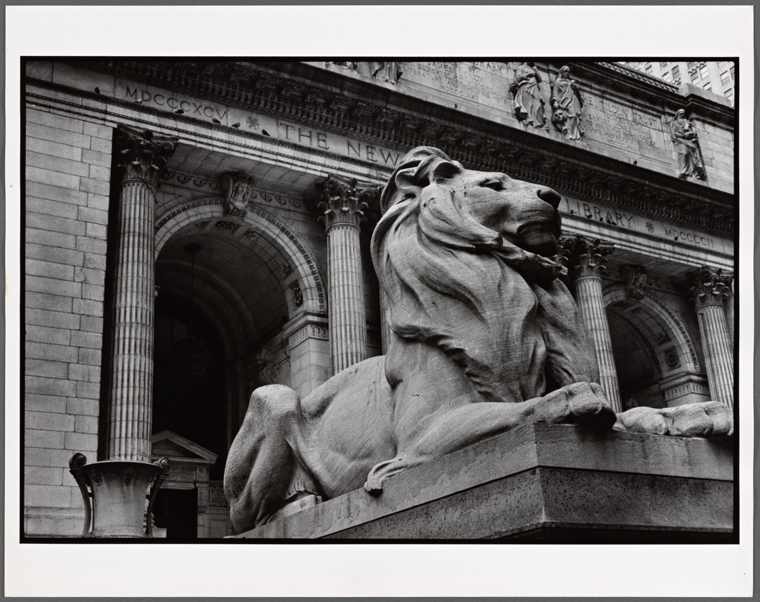

Often referred to as the "main branch," the Beaux-Arts landmark building on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street houses outstanding research collections in the humanities and social sciences. The non-circulating graduate-level collections were initially formed from the consolidation of the Astor and Lenox Libraries, and have evolved into one of the world's preeminent public resources for the study of human thought, action, and experience—from anthropology and archaeology to religion, sports, world history, and literature.

The Library is restoring the Schwarzman Building to its original purpose of providing library services for “the free use of all the people.” Learn more about the Midtown Campus Renovation.

While the Schwarzman Building does not house circulating collections, just across the street, at 40th Street and Fifth Avenue, you can visit the fully renovated Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (SNFL), our largest circulating branch. Visitors are welcome to explore and use nearly all of the building’s services and resources, including unlimited browsing, seating, computer access, the free publicly accessible rooftop terrace, and more. Learn more.

The Stephen A. Schwarzman Building is renowned for the extraordinary comprehensiveness of its historical collections as well as its commitment to providing free and equal access to its resources and facilities. It houses some 15 million items, among them priceless medieval manuscripts, ancient Japanese scrolls, contemporary novels and poetry, as well as baseball cards, dime novels, and comic books.

Stephen A. Schwarzman Building History

Collecting the rare and the commonplace, the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building has, since the beginning, acquired materials regarded as controversial—even offensive—by some. During the height of McCarthyism in the late 1940s, we actively took in materials from the left and the right, despite the objections of government and citizens' patriotic groups.

The ways in which the resources of the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building have been used are as diverse as the collections themselves:

- During World War II, Allied military intelligence used the Map Division for research on the coastlines of countries in the theater of combat.

- Television and print journalists first consulted the Slavic and Baltic Division when covering the changing political structure of the former Soviet Union.

- Authors of countless literary and nonfiction books cite the Library as a major resource in their work.

- Countless individuals have reconstructed family histories and located long-lost relatives through records in the Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History, and Genealogy.

The origins of this institution date back to the time when New York was emerging as one of the world's most important cities. By the second half of the 19th century, New York had already surpassed Paris in population and was quickly catching up with London, the world's most populous city. Fortunately, this burgeoning and somewhat brash metropolis understood that if New York was to become one of the world's great centers of urban culture, it must have a great library.

A prominent proponent was one-time governor Samuel J. Tilden (1814–1886), who bequeathed the bulk of his fortune, about $2.4 million, to "establish and maintain a free library and reading room in the city of New York." At the time of Tilden's death, New York already had two libraries of importance: the Astor and Lenox, but neither could be termed a public institution in the sense that Tilden envisioned.

The Astor Library was created through the generosity of John Jacob Astor (1763–1848), a German immigrant, who, at his death, was the wealthiest man in America. In his will he pledged $400,000 for the establishment of a reference library in New York. The Astor Library opened its doors in 1849, in the building that is now the home of The New York Shakespeare Festival's Joseph Papp Public Theater. Although the books did not circulate and hours were limited, it was a major resource for reference and research.

New York's other principal library was founded by James Lenox, and consisted primarily of his personal collection of rare books (which included the first Gutenberg Bible to come to the New World), manuscripts, and Americana. Located on the site of the present Frick Collection, the Lenox Library was intended primarily for bibliophiles and scholars. While use was free of charge, admission tickets were required.

By 1892, both libraries were experiencing financial difficulties. The combination of dwindling endowments and expanding collections had compelled their trustees to reconsider their mission. John Bigelow, a New York attorney and Tilden trustee, devised a bold plan to combine the resources of the Astor and Lenox libraries and the Tilden Trust to form The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Bigelow's plan, signed on on May 23, 1895, was hailed as an unprecedented example of private philanthropy for the public good.

The site chosen for the home of the new Public Library was the Croton Reservoir, a popular strolling place that occupied a two-block section of Fifth Avenue between 40th and 42nd Streets. Dr. John Shaw Billings, one of the most brilliant librarians of his day, was named director.

Billings knew exactly what he wanted. His design, briefly sketched on a scrap of paper, became the early blueprint for the majestic structure that has become the landmark building, known for the lions without and the learning within. Billings's plan called for an enormous reading room topping seven floors of stacks and the most rapid delivery system in the world to get the Library's resources as swiftly as possible into the hands of those who requested them.

Following an open competition among the city's prominent architects, the relatively unknown firm of Carrère & Hastings was selected to design and construct the new library. The result, regarded as the apogee of Beaux-Arts design, was the largest marble structure ever attempted in the United States. Before construction could begin, however, some 500 workers had to spend two years dismantling the reservoir and preparing the site. The cornerstone was finally laid in place on November 10, 1902.

In the meantime, the Library had established its circulating department after consolidating with The New York Free Circulating Library in February 1901. A month later, steel baron Andrew Carnegie offered $5.2 million to construct a system of branch libraries throughout New York City, provided the City would supply the sites and fund the libraries' maintenance and operations. Later that year The New York Public Library contracted with the City of New York to operate 39 Carnegie branches in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island. From the beginning The New York Public Library established a tradition of partnership with the city and outreach to the community, which continues to today.

In the meantime, the Library had established its circulating department after consolidating with The New York Free Circulating Library in February 1901. A month later, steel baron Andrew Carnegie offered $5.2 million to construct a system of branch libraries throughout New York City, provided the City would supply the sites and fund the libraries' maintenance and operations. Later that year The New York Public Library contracted with the City of New York to operate 39 Carnegie branches in the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island. From the beginning The New York Public Library established a tradition of partnership with the city and outreach to the community, which continues to today.

On Fifth Avenue, work progressed slowly but steadily on the monumental Library, which would eventually cost $9 million to complete. During the summer of 1905, the huge columns were put into place and work on the roof was begun. By the end of 1906, the roof was finished and the designers commenced five years of interior work. In 1910, 75 miles of shelves were installed to house the immense collections.

More than one million books were set in place for the official dedication of the Library on May 23, 1911—exactly 16 years after the historic agreement creating the Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations had been signed. The ceremony was presided over by President William Howard Taft and was attended by Governor John Alden Dix and Mayor William J. Gaynor.

The following morning, New York's very public, Public Library officially opened its doors. The response was overwhelming: between 30,000 and 50,000 visitors streamed through the building the first day. One of the very first items called for was Nravstvennye idealy nashego vremeni (Moral ideas of our time) by Nikolai I. Grot, a study of Friedrich Nietzsche and Leo Tolstoy. The reader filed his slip at 9:08 AM and received his book seven minutes later!